Absence and presence: collectivity and resistance in art

In celebration of Women’s History month, guest writer Riya Kumar has chosen five works of art from the Collection that play with ideas of women’s absence and presence, and shed light on moments of their resistance, reclamation and collectivity.

Johann Zoffany (artist), Richard Earlom (engraver), The Royal Academy of Arts, instituted by the King, in the Year 1768, 1773

This print, after an original painting by Johann Zoffany which is in the Royal Collection, commemorates all but three of the 36 founding members of the Royal Academy (RA). We can see Zoffany, who was also a member of the RA, at the bottom left of the image, looking out and establishing himself as its creator.

Amidst Greek and Roman busts, hang two paintings of women: Mary Moser and Angelica Kauffman. They were the only two founding women members of the Royal Academy. The reason they have been excluded from this print is perhaps a result of the setting as it was considered improper for women to take part in life drawings.

The inclusion of women as founder members of the Academy was not complete – neither Moser nor Kauffman were allowed in the Council and therefore had no influence on how the Academy was governed. While both were well-known artists of their time, this print suggests that they remained a distance away from their male counterparts.

Sally Payen, Fence and Shadow, Invisible Woman and the Telephonic Tree, 2016–17

Five red roses are placed on a rickety patched up wire fence. A helicopter looms in the distance. There are no tangible traces of human figures yet Sally Payen’s painting represents a moment of women’s resistance and collectivity.

In 1981, a group of women marched from Cardiff to the Greenham Common Air Base in Berkshire to protest the use of what was once common land as a base for US missiles. The women set up the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, often gathering in large numbers around the base to protest.

The red flowers reference the natural world under threat from nuclear contamination. The yarns of wool interspersed with the wire fence evoke the children’s clothes that women knitted and attached to the fence. These acts become markers of the protest.

In Payen’s work, we do not see these women. But we see traces of what they left behind, what they fought for and a legacy of resistance against nuclear weapons that lives on, even today.

Jasleen Kaur, Women Hold Up Half The Sky, 2019

When Jasleen Kaur was looking into Sikh and Punjabi colonial histories, she found a photograph of members of the 2nd Royal Battalion of the British Indian Army in a gymnastic display. During the period between 1857 and 1940, the British developed a pseudo-scientific martial race theory in which men from certain ethnic groups or castes were deemed more fit for warfare. The Sikhs, according to the British, fell under this category.

At first glance, this print, which started as a billboard work by Kaur, is about spectacle and physical strength. However, this reimagined composition, and the way it has been altered through the insertion of hands – Kaur’s mother’s hand – brings overlooked histories to the surface.

Kaur’s practice is embedded in research. She is interested in how colonialism has affected gender roles and ideas of masculinity and femininity. The hint of a woman’s presence through her mother’s hands, and the absence of a physical female figure, mirror how women’s labour and contributions often go undocumented.

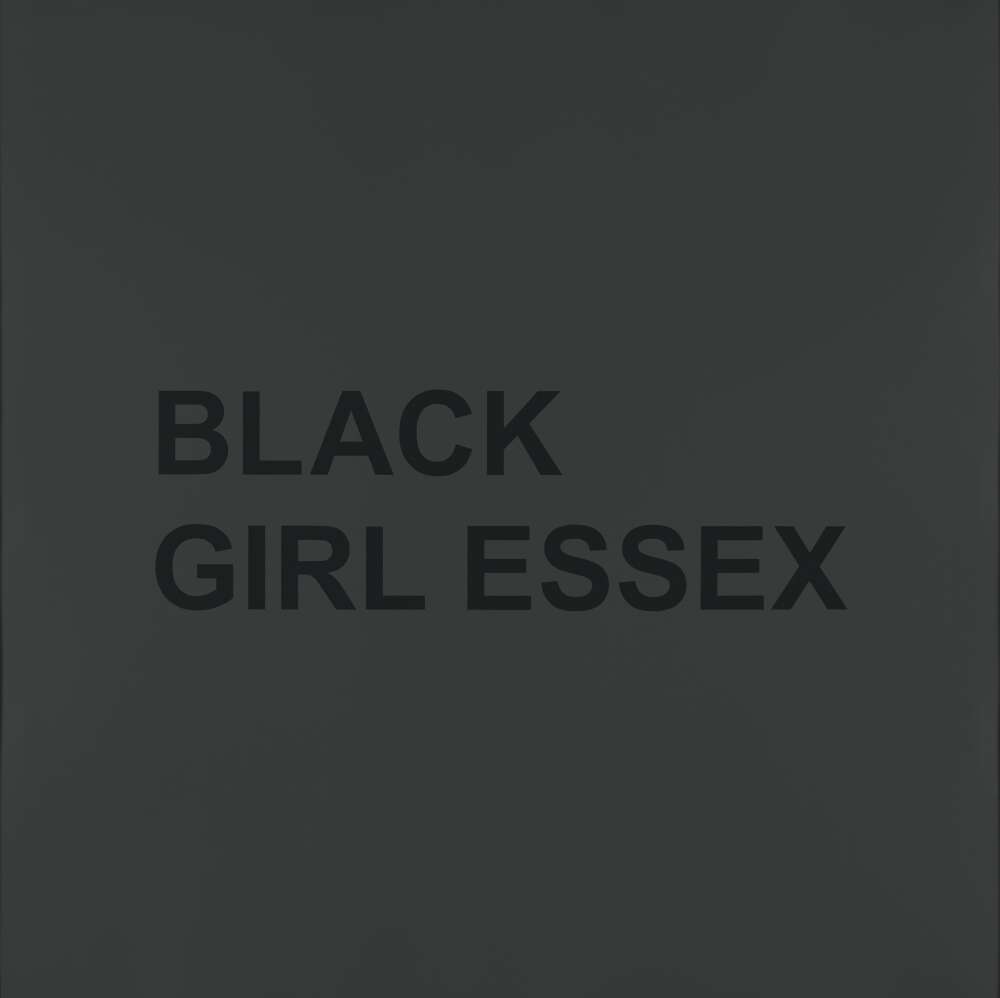

Elsa James, Work No. 4: Hey, we’re over here!, 2021

In December 2020, the term ‘Essex girl’ was removed from the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. The pejorative phrase described young women who lived in Essex as ‘unintelligent, promiscuous and materialistic’.

As an Essex resident since 1999, Elsa James’ work centres Blackness and her lived experience. She explores the lesser-known histories of Essex often concealed by white-centric narratives.

In this work, James reclaims a once pejorative term with explorations of race, gender and Black subjectivity. The black text blends into the background, playing with ideas of visibility and invisibility. The artwork forces a viewer to adjust their body to read the text. James likens this to her ancestors who were constantly on the move, taken from Africa to British colonies in the Caribbean.

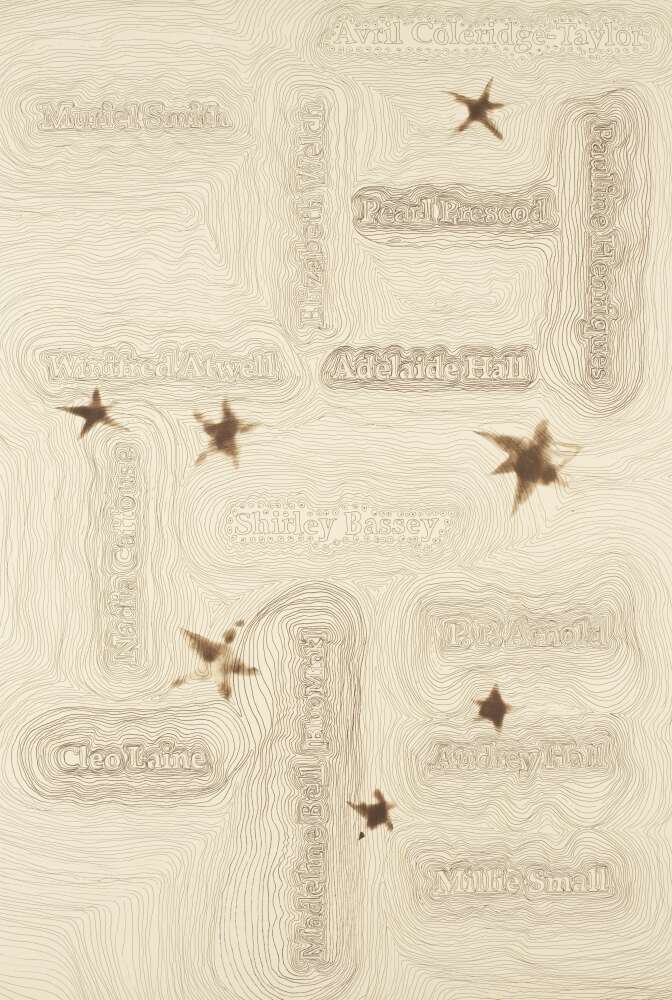

Sonia Boyce, 1930s to 1960s, 2006

Muriel Smith, Avril Coleridge-Taylor, Elizabeth Welch, Pearl Prescod, Pauline Henriques, Adelaide Hall, Winifred Atwell, Nadia Cattouse, Shirley Bassey, P.P. Arnold, Audrey Hall, Madeline Bell (Blue Mink), Cleo Laine, Millie Small… Sonia Boyce brings together and draws connections between 14 women performers. Active during the 20th century, these women were often overlooked and forgotten because of their race.

Musicality seeps through this print. The circular shapes that enclose the names of Shirley Bassey and Avril Coleridge-Taylor remind us of vinyl CDs and grooves. The stars appear hazy, perhaps mirroring the transient nature of stardom or the gradual fading of these women from memory.

Boyce’s work draws from conversations she has had with women about their memories of Black women singers. By naming them, she brings them back into public consciousness.

Riya Kumar is currently pursuing an MA in Curating at Courtauld Institute of Art. Previously, she worked as a Curatorial Assistant at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru, contributing to exhibitions and digital projects. Her research interests lie in questions of classifications and conceptions of modernity and indigeneity within the context of Indian visual culture. She received her B.A. in Psychology from Claremont McKenna College in California.