Women artists shaping British art

To celebrate Women’s History Month, Curator Shasti Lowton highlights three works recently added to the collection by female artists who are shaping the face of British art.

Rana Begum

Rana Begum, 1163-80 Foil, 2022 © Rana Begum

Rana Begum’s Foil series explores the perception of light, colour and form, blurring boundaries between painting, sculpture, architecture and design. Her use of repetitive geometric patterns (found both within Islamic art and the industrial cityscape) takes its inspiration from childhood memories of the rhythmic repetition of daily recitals of the Qur’an. Made from spray-painted aluminium foil, Begum uses hand-folding, unfolding and scrunching to create a more organic geometry. The resulting three dimensional surfaces shift our perspective, and, when combined with the vividly coloured hues of each work, seem to manipulate the light.

The combined effects evoke a collection of reflective landscapes that seem otherworldly. Through her work, Begum creates a temporal and sensorial experience that encourages us to pause and look closer. Begum’s experimentation with different mediums invites us to challenge our understanding of light and colour, presenting us with a moment of calm and wonder wherever her work is displayed.

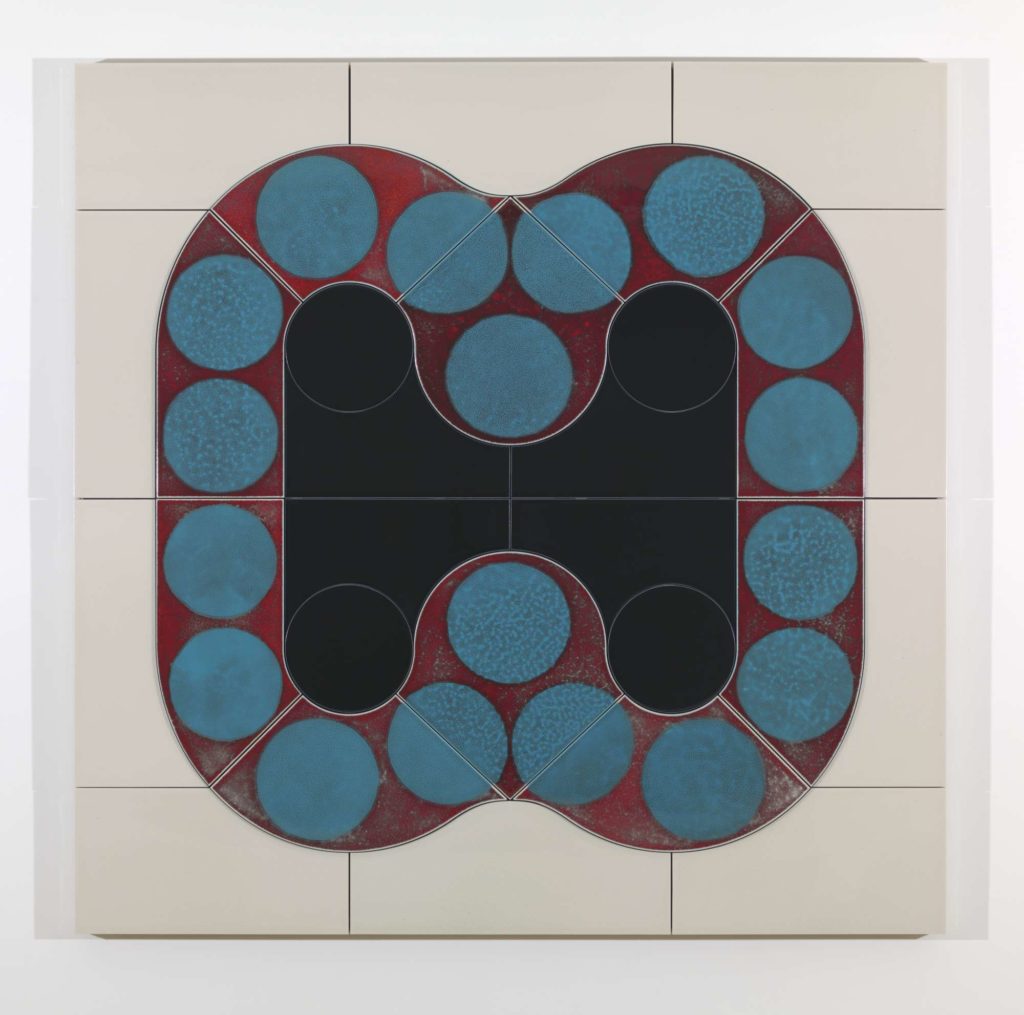

Lubna Chowdhary

Lubna Chowdhary creates sculptural objects and site-specific artworks primarily in the field of ceramics. Sign 12 combines industrial tile modules with a laborious hand-glazing process. The smooth, undulating textures of the glazes contrast with Chowdry’s choice to use precise machine cutting, allowing her to disrupt the common grid-like appearance of standard tiles to create a complex geometry. Her flowing shapes and instinctive use of vivid colours are inspired by a diverse range of artistic and cultural influences including Islamic architecture, Hindu temples and modernist design. Chowdhary combines these to represent the multiple layers of her own identity which incorporates Pakistani, Tanzanian and British influences. This lends to her experience as an artist operating in both the Asian and African diasporas.

Lubna Chowdhary, Sign 12, 2022 © Lubna Chowdhary

When Chowdhary stumbled into the field of ceramics on the 3D design degree she had enrolled on, she initially distanced herself from the medium due its domestic associations. At the time, the art sector at large had labelled ceramics ‘a crafty, feminine pursuit’. For Chowdhary: ‘it was the sort of pursuit I was trying to escape and distance myself from. Much as I tried to resist, I was seduced by the immediacy of clay. It’s a material that can be shaped without the use of machinery or tools and it responds directly to your hands, allowing you to create forms almost as you conceive them.’

Charmaine Watkiss

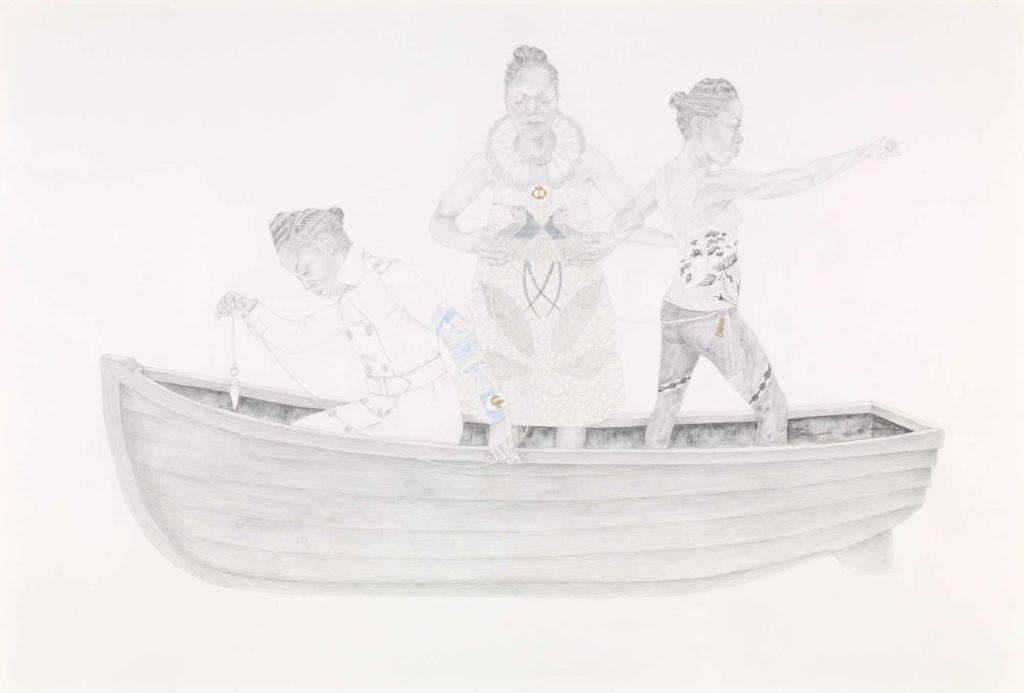

Charmaine Watkiss’s intricate pencil drawing The Passengers tells a powerful story of the migration and legacy of the Windrush generation, questioning ideas around sovereignty and what constitutes Britishness.

The three figures in the piece are self-portraits that contain elements from three of her previous works. The kneeling figure to the left is an evolution of Watkiss’s earlier work Lost/Found, an excavation into London’s maritime past and the creation of the City of London financial district. Starting with a simple question – ‘Why is Jamaica Road in Bermondsey called Jamaica Road?’ – Watkiss uncovered the history of the borough of Southwark’s participation in the transatlantic slave trade. By allowing the import of goods (particularly tobacco and sugar) along its docks, Southwark played a major role in creating the wealth in the commercial district of London that we recognise today. On the sleeve of the kneeling figure, Watkiss has included architectural imagery from buildings in London’s financial district.

Charmaine Watkiss, The Passengers, 2020 © Charmaine Watkiss. All rights reserved, DACS 2023.

The central figure originates from Watkiss’s work The World Has Four Corners, a poignant piece that reminds us that the Black community can be found all over the world. Two hummingbirds (the national birds of Jamaica) are depicted in the fabric of the central figure’s dress subtly referencing Watkiss’s Jamaican heritage. The island of Jamaica was often the last stop on transatlantic slave trade routes. The treacherous nature of the journey and inhumane conditions endured by Africans aboard the ships (which made multiple stops across the Americas and the Caribbean) meant that only a few survived until this final stop. The Taínos (a historic indigenous community in the Caribbean) considered hummingbirds a symbol of transformation and rebirth, a process that both the island and community of Jamaica has gone through tenfold. Hummingbirds are also known to be fierce fighters and defenders of their territory.

The figure to the right of the work is drawn in a patterned outfit that Watkiss first included in her work They Didn’t Come Here to Stay. The original work tells the story of the generation of Watkiss’s parents’ arrival to the UK. Using the imagery of the Three Graces from Greek mythology, Watkiss describes the journey of arrival, discord and settlement. The pattern used in both these works is a William Morris design called Windrush that was created in 1883. The pattern was one of thirteen created by Morris that were named after tributaries (fresh water streams that feed into a larger river) of the Thames. It features large flower heads that resemble peonies overlapping with smaller plants and scrolling foliage. Watkiss’s inclusion of this pattern within her work perhaps alludes to the Windrush community’s rejuvenation of London following the Second World War.

All three figures in The Passengers are connected by the long thread of a scrying pendulum. This tool of divination has been used since the 17th century to elicit spiritual guidance, make decisions, answer questions and cleanse negative energy. Pendulums have also been used to locate lost objects; the positioning of the pendulum towards the bottom of the boat suggests that the three figures are looking for direction and guidance from the many Africans who either jumped or were thrown overboard from slave ships.

Through her use of drawing, a primary language and technique in the art making process, Watkiss is able to load her work with symbolism.