Art and identity: South Asian Heritage Month

As a geographical area South Asia spans Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. However, with a community presence in every continent, the reach and influence of the South Asian diaspora is global. Within the UK, South Asian contributions have been particularly important in shaping food, fashion, music, art and wider popular culture; they now define what it means to be quintessentially British. To celebrate South Asian Heritage Month (17 July – 18 August), Curator Shasti Lowton highlights artworks in the Collection by artists from the diaspora.

Sutapa Biswas

Sutapa Biswas’ works are shaped by her observations of the relationships between people and the places they live in. Born in India and educated in the UK since she was four years old, she is especially interested in how larger historical narratives collide with personal ones. Her work first came to prominence when she was part of the landmark exhibition The Thin Black Line (1985) curated by Lubaina Himid. This exhibition marked the arrival of a radical generation of young Black and Asian women artists on the British art scene. They challenged their collective invisibility in the art world and engaged with the social, cultural, political and aesthetic issues of the time.

These photographic works are still images from the artist’s film Lumen. A semi-fictional film, it tells the story of the Biswas’ family’s sea voyage to England. In it, the artist’s personal history of migration overlaps with other maritime histories, from the Atlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades, to post-emancipation British colonial trade and post-colonial migration. Both Biswas’s mother and grandmother were displaced due to Partition. Biswas felt that her mother’s subsequent journey to the country that caused the trauma and violence of Partition was a story that needed to be told.

The starting point for this work is Vermeer’s painting Woman in Blue Reading a Letter. When Biswas came across a photograph of Vermeer’s work, she was immediately flooded with memories of her mother standing by a window in England, weeping as she read letters sent from home.

The stills above were shot inside the rich interiors of The Red Lodge Museum, Bristol Museums, that housed prominent Bristolians associated with the slave trade and the British abolitionist movement. The circular mirror in Lumen perhaps alludes to the project’s title as both a unit of light and a conduit into the matriarchal bloodline of the Biswas family. In All the Apples, we see the film’s protagonist laying on the floor of the museum surrounded by apples, a fruit laden with symbolism. Here, they seem to relate to the products and produce catalogued by the British East India Company, allowing them to heavily tax Indian British subjects. Although more commonly associated with an English orchard, apples have been recorded as existing in India since the early 1300s. Today the Indian State of Himachal Pradesh is believed to produce 20 per cent of the world’s apples.

Chila Kumari Singh Burman

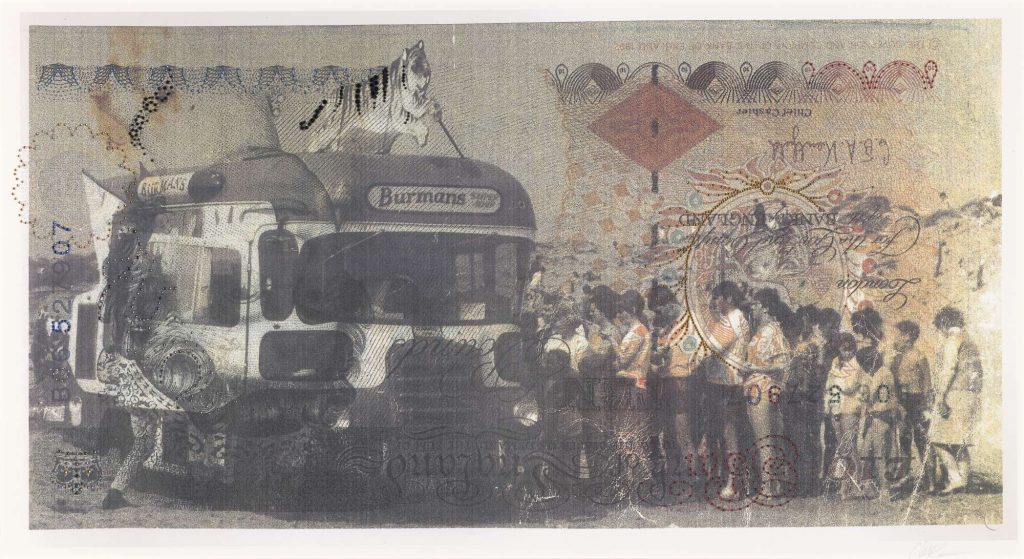

Chila Kumari Singh Burman, BENGAL TIGER VAN – Raspberry Ripples, Chila’s Dad selling ice-cream on Freshfield Beach, Merseyside 1976, 2018 © Chila Kumari Singh Burman

Burman is perhaps best known for her dramatic neon installations, such as Remembering a Brave New World which lit up the exterior of Tate Britain in the winter of 2020. Since the mid-1980s she has explored the experiences and aesthetics of what she describes as ‘South Asian feminisms’. Working across painting, photography, installation, printmaking, video and film, she challenges South Asian female stereotypes, exploring the intersections of gender, class and ethnicity in the construction of identity. Born in Bootle, Merseyside to Punjabi-Hindu parents who emigrated to England in the 1950s, Burman was part of a generation of Black British artists whose parents had settled in post-war Britain.

Printed over an enlarged upside down £10 bank note, this image of holidaymakers queuing up beside an ice cream van is a vivid memory for the artist. A spectacular cut-out Bengal tiger frozen mid-pounce, sits atop the van, its stripes embellished in black crystals. This was the iconic symbol of ‘Burman’s’, the business owned by the artist’s father in 1960s Liverpool.

A common motif in Burman’s work, the tiger is playful, but also directly links to her cultural roots. As the national animal of India the tiger is representative of grace, strength, agility and enormous power. In Hindu mythology the goddess Durga is depicted riding a tiger, symbolic of the unlimited power that she wields to destroy evil and bring goodness into our lives. The colourful Swarovski crystal transfers on the print allude to the decorative elements on Indian saris and textiles.

Burman relates this work directly to a childhood ‘filled with confectionery’, and the weekends she spent helping her father in the ice cream van. In the print, his presence is suggested by the appearance of a leg climbing into the driver’s side of the van. The rest of his body concealed behind the neatly coiffed hair of Queen Elizabeth II on the banknote. Ice cream ensured the Burman family’s livelihood, but also established a strong identity in 1960s Liverpool, where many members of the Indian community ran ice cream businesses.

Sunil Gupta

An artist, filmmaker, curator and writer, Sunil Gupta advocates for queer identity and freedom in his practice. He was an active figure in London in the 1980s, notably through his contributions to the Black British Arts movement and his role in establishing Autograph ABP (Association of Black Photographers). In his photographs, Gupta explores the identity of people marginalised due to their race, sexuality or country of origin.

Born in India, Gupta emigrated with his family to Canada where, as a teenager, he discovered his homosexuality and became increasingly drawn to photography. He moved to London (by way of New York) to study the subject further.

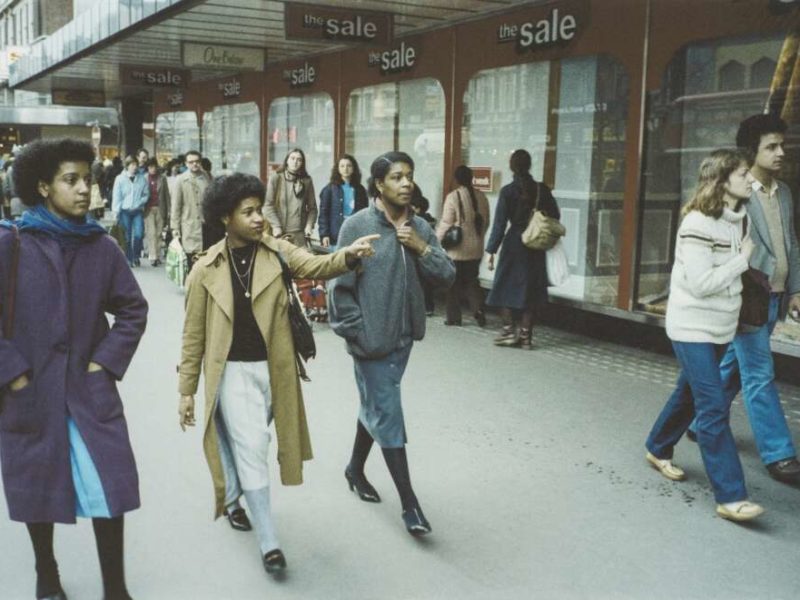

These photos are part of London, a 1982 series of 60 street scenes; they are poetic observations of class, age and race in urban multicultural London. In the early 1980s, Sunil Gupta enrolled at the Royal College of Art and took to the streets of the capital to find London’s gay life around Earl’s Court, King’s Road, and the West End.

Even what appeared to be a concentration of gay life was not dense enough to create its own public space, so I was getting either huge gaps between people or a crowd of very mixed people. I decided to abandon an exclusively gay subject and started concentrating on whatever caught my eye — migrants, people of colour, gay men, elderly people out and about on their own.

Gupta was alert to the difficulty of navigating Britain as an openly gay Asian man in the 1980s, a period when racial tension and homophobia were at an all time high. He has mentioned how different this was to his first foray into street photography as a student in New York, where his first photographic series recorded the gay liberation movement around Christopher Street in Manhattan, the site of the legendary Stonewall Inn. Gupta’s London scenes are acute observations of class, age and race in the urban multicultural London of the 1980s.

Matthew Krishanu

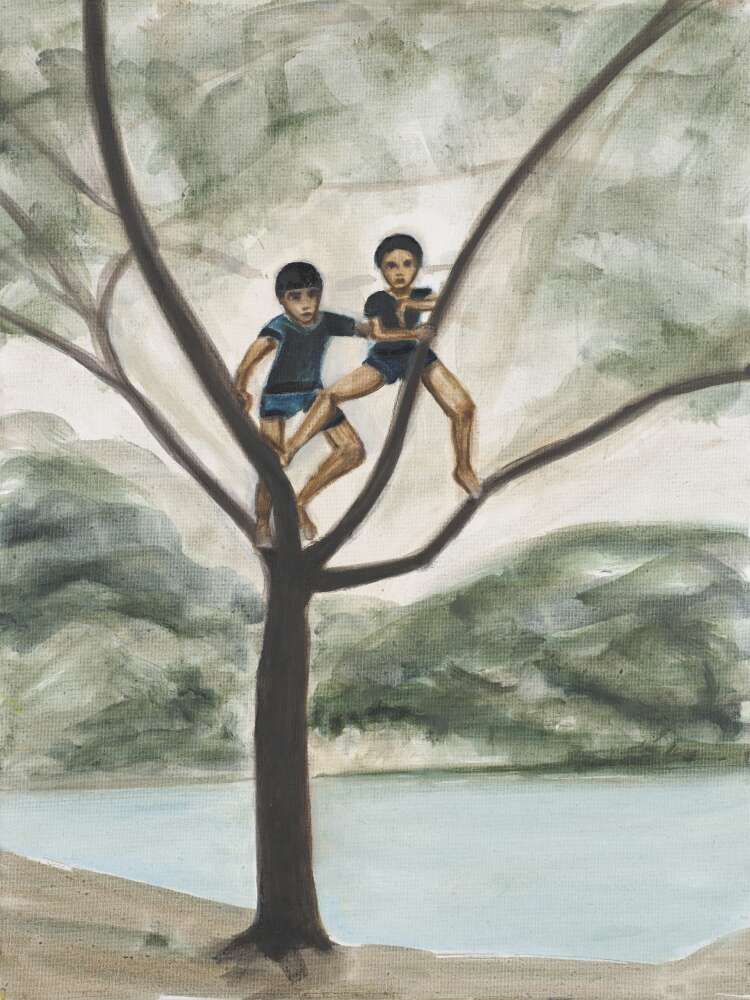

Matthew Krishanu, Two Boys in a Tree, 2018 © Matthew Krishanu

Matthew Krishanu’s paintings offer a nuanced exploration of cultural identity, memory and personal experience. Born in Bradford to an Indian mother and a white English father, the family moved to Bangladesh before returning to the UK when he was 12 years old. Krishanu’s work draws on specific photographic images, including those that document his family and childhood in Bangladesh.

Mountain Tent and Two Boys in a Tree present him first as a young boy reading in front of a tent against a mountainous landscape; and second, climbing a tree with his older brother. Many of Krishanu’s paintings capture the childhood gaze of these early experiences and the distinctive bond between the artist and his sibling.

Recurrent themes in his work include family and grief, religion and race, childhood and memory, with many of his paintings representing his early years in Bangladesh. The idyllic representation of this childhood memories perhaps illustrate Krishanu’s longing to return to that specific moment in time.

Prem Sahib

Born in London, Sahib grew up in Southall, an area known for its predominantly Punjabi community. He is best known for his minimalist sculptures which contain narratives that Sahib identifies as ‘a lurking presence’. They explore themes related to sexual identity and queer culture.

Stone presents a drinking fountain contained within a block of shimmering blue resin. It replicates the fountains once installed at Chariots, a well known gay sauna in London, which had to close its flagship branch in Shoreditch after almost 20 years of operation, to make way for a luxury hotel development.

Prem Sahib’s work merges ideas of personal and public spaces, sexuality and desire. Along with reproducing the drinking fountain from Chariots, Sahib also salvaged twelve of the original lockers from the sauna which he presented as sculptures. Inside many of the lockers were stickers of work by gay street artists, information on contacting housing association helplines and public health campaigns including the Do you care? We do condom campaign from the 1990s which became the title of the work. Together, this body of work highlights the importance of preserving safe spaces for marginalised communities to express themselves and the important role these venues can play in communicating life saving information to those in need.