Journeys of the heart: the UK and the Holy See

2022 marked 40 years of full diplomatic relations between the UK and The Holy See. A new display by the Collection celebrates this relationship, addressing themes such as pilgrimage, church history and aspects of contemporary life with references from literature, music and religion.

Whether real or imaginary, pilgrimages have been a common feature of many world religions. They allow us to reconnect with the past and to explore different cultures, beliefs, rituals and geographies. The works of art in this display evoke different types of pilgrimages.

Giuseppe Vasi, Il Prospetto Principale del Tempio e Piazza di S. Pietro in Vaticano, 1774

Religious Pilgrimages

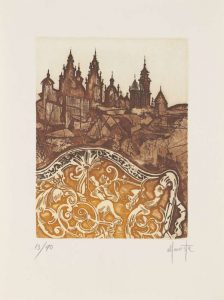

Alfonso Costa, Compostela é unha rúa longa… (Santiago de Compostela), 1989 © Alfonso Costa

Alongside St Peter’s Basilica, Santiago de Compostela in Spain is one of the most significant pilgrimage sites of Christendom. Alfonso Costa’s prints offer a glimpse into a pilgrim’s perspective as they approach the medieval cathedral to pay homage to the relics of the apostle St James. Like a companion along the way, each of Costa’s prints is paired with a poem, transforming the Camino de Santiago routes into a sensorial experience where people meditate, pray, connect with nature, spend time in silence or reminisce:

Compostela is a long street

in the memory

where the names

and the hours wander

that everyone remembers

…………………………….

Just like waves

the memories become loose

from the depths of us

making a sea that moves away.Salvador García-Bodaño Zunzunegui, translation of Compostela é unha rúa longa, 1989

‘A sea that moves away’ is also evoked in Ceri Richards’ watercolours from the series La Cathédrale Engloutie. Richards’ works are inspired by Claude Debussy’s 1910 piano prelude of the same title, and reference a Breton legend about the cathedral of Ys whose bells and organ could still be heard echoing from the depths of the sea which had engulfed it. A pianist himself, Richards includes motifs such as a pilgrim’s scallop shell, a chalice, a rosary and a cross juxtaposed with music sheets, all slightly distorted as if seen through water. Pilgrims often carried some of these objects as a way to establish an identity and to receive guidance and protection along the journey.

Almost like a reliquary with precious fragments unfolding gradually, Graham Gingles’ The Kiss is a repository of found objects which evoke personal memories, stories and feelings. Presented as a triptych giving it a religious aura, this intricate theatrical construction box is a subtle meditation on life and death:

‘…this piece is a memorial for a dead friend. I am interested in what we leave behind after we die, even small trivial things like the blotted lipstick print of lips on a piece of paper. The Victorians were very good at this with their mourning jewellery…The top half has a printed image of a rose, actually the last rose she was given before she died.’ Graham Gingles

Spiritual Pilgrimages: a change of heart

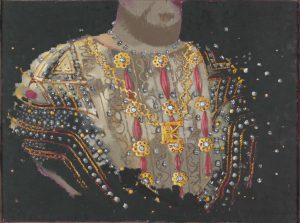

Stephen Farthing, Bling! Henry, 2007 © Stephen Farthing

A pilgrimage can also be a symbolic journey undertaken with no specific destination in mind. In some cases, it can be driven by political decisions, and the journey itself becomes a quest for self-affirmation, power and authority.

King Henry VIII was a devout Catholic. He attended daily Mass and went on Catholic pilgrimages to holy sites, such as the shrine to Our Lady of Walsingham, in Norfolk. In 1521, Pope Leo X conferred Henry VIII the title ‘Defender of the Faith’ as a reward for his theological treatise against the Protestant Reformation leader Martin Luther. However, in 1534 a major shift took place when Henry VIII declared himself the head of the Church in England, resulting in England’s Reformation. Stephen Farthing’s contemporary take on Henry VIII’s portrait is a bold and humorous interpretation of the ‘headless sitter’ – a reference to his turbulent marriages – making it instantly recognisable through visual clues such as the glimpse of a beard and elaborate, jewelled costume.

Literary Pilgrimages

Ithell Colquhoun, Scene from Marlowe’s ‘Dr Faustus’, 1933 © Estate of the Artist

Westminster Abbey’s Poets Corner is a place of pilgrimage for literature enthusiasts, encapsulating a gallery of monuments dedicated to the history of British literature, from Geoffrey Chaucer to Ted Hughes. The artworks in this section reference literary sources from around the world. Dwelling on the theme of imaginary pilgrimages in search of salvation are works inspired by Dante’s Divina Commedia, Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, John Milton’s Paradise Lost and Persian calligraphy and cosmography.

Artistic Pilgrimages

David Roberts, Interior of St. Peter’s, Rome, 1853-4

Between the 17th and the early 19th century, English collectors and artists travelled to Italy as part of the Grand Tour with the aim to immerse themselves in the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance. David Roberts’ painting captures a group of pilgrims in prayer before the statue of St Peter’s, a sight we can still witness today, as in 1853 when the artist visited the Basilica. During their travels, British artists such as William Marlow and Roberts would have admired and copied Italian Renaissance paintings by the most celebrated artists including Raphael and Andrea Schiavone.

Contemporary World

Liam Gillick, Related Faction, 2007

Pilgrimages and journeys are not always smooth. They are often about going to an unknown or foreign place, in search of new or transformational meaning. They are also about what one leaves behind – a family, feelings, places, stories, possessions. The works in this section encourage reflection on global issues.

Liam Gillick’s sculpture Related Faction stands as a metaphor for conversation and how people interact in different social environments. Each of its colourful, distinctive horizontal lines that dominate both parts of the sculpture resembles lines from a dialogue exchange where topics could include: status and power, forced migration, displacement and the consequences of climate change. Lubaina Himid’s Old Boat, New Weather recounts the story of the transatlantic slave trade where the boat which shelters the monumentalised barn-like structure, is a place of refuge, a protective ark. The multi-coloured grid which makes up the sky signals to an uncertain future where climate change will cause mass displacement: a delicate line between safety and danger.